Born to Run: the Slave Family in Early New York

The first slave auction in New Amsterdam in 1655, painted by Howard Pyle, 1917

The enslavement of African people in the United States continued in New York as role of the Dutch slave merchandise. The Dutch West India Visitor imported eleven African slaves to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the kickoff slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655.[1] With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies (later on Charleston, S Carolina), more than 42% of New York City households held slaves by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers.[two] Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Slaves were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, besides equally the Mohawk Valley region.

During the American Revolutionary War, the British troops occupied New York City in 1776. The Philipsburg Announcement promised freedom to slaves who left rebel masters, and thousands moved to the city for refuge with the British. By 1780, x,000 black people lived in New York. Many were slaves who had escaped from their slaveholders in both Northern and Southern colonies. Later the war, the British evacuated almost 3,000 slaves from New York, taking well-nigh of them to resettle as complimentary people in Nova Scotia, where they are known as Black Loyalists.

Of the Northern states, New York was next to concluding in abolishing slavery. (In New Bailiwick of jersey, mandatory, unpaid "apprenticeships" did not cease until the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery, in 1865.)[3] : 44

Afterwards the American Revolution, the New York Manumission Gild was founded in 1785 to piece of work for the abolition of slavery and to aid free blacks. The land passed a 1799 constabulary for gradual abolition, a law which freed no living slave. After that appointment, children born to slave mothers were required to work for the female parent'south chief as indentured servants until historic period 28 (men) and 25 (women). The last slaves were freed of this obligation on July 4, 1827 (28 years later 1799).[ane] African Americans celebrated with a parade.

Upstate New York, in contrast with New York City, was an anti-slavery leader. The starting time coming together of the New York Land Anti-Slavery Order opened in Utica, although local hostility caused the meeting to exist moved to the habitation of Gerrit Smith, in Peterboro. The Oneida Plant, near Utica, briefly the center of American abolition, accepted both blackness and white male enrolees on an equal basis. New-York Central College, most Cortland, was an abolitionist institution of college learning founded by Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor, that accepted all students without prejudice. It was the beginning college to have blackness professors teaching white students. However, when a black male kinesthesia member, William G. Allen, married a white educatee, they had to abscond the country for England, never to return.

Dutch rule [edit]

Jacob van Meurs, Novum Amsterodamum [New Amsterdam], 1671. In the middle of the picture show a man hangs by his centre, suspended past a hook in his ribs, a usual punishment for runaway slaves.

Initial grouping of slaves [edit]

In 1613, Juan (Jan) Rodriguez from Santo Domingo became the showtime non-indigenous person to settle in what was and so known as New Amsterdam. Of Portuguese and Due west African descent, he was a free man.[iv]

Systematic slavery began in 1626, when 11 captive Africans arrived on a Dutch West India Visitor ship in the New Amsterdam harbor.[5] [4] Historian Ira Berlin called them Atlantic Creoles who had European and African beginnings and spoke many languages. In some cases, they attained their European heritage in Africa when European traders conceived children with African women. Some were Africans who were crew members on ships and some came from ports of the Americas.[half dozen] [a] Their commencement names—like Paul, Simon, and John—indicated if they had European heritage. Their terminal names indicated where they came from, like Portuguese, d'Congo, or d'Angola. People from the Congo or Angola were known for their mechanical skills and docile manners. Vi slaves had names that indicated a connectedness with New Amsterdam, such every bit Manuel Gerritsen, which he likely received after their arrival in New Amsterdam and to differentiate from repeated first names.[half-dozen] Men were laborers who worked the fields, built forts and roads, and performed other forms of labor.[5] According to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem adopted from southern colonies, children built-in to enslaved women were considered born into slavery, regardless of the ethnicity or condition of the father.[1]

In Feb 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned Willem Kieft, the director general for the colony, for their freedom. This occurred during a fourth dimension where there were skirmishes with Native American people and the Dutch wanted blacks to help protect their settlements and did not want the slaves to join the Native Americans. These xi slaves were granted partial freedom, where they could buy country and a home and earn a wage from their master, and so total freedom. Their children remained in slavery. By 1664, the original xi slaves, equally well every bit other slaves who had attained half-freedom, for a total of at least 30 blackness landowners, lived on Manhattan near the Fresh H2o Pond.[7] [4]

Slave trade [edit]

For more than ii decades after the start shipment, the Dutch West India Company was dominant in the importation of slaves from the coasts of Africa. A number of slaves were imported directly from the visitor's stations in Angola to New Netherland.[5]

Due to a lack of workers in the colony, information technology relied upon on African slaves, who were described by the Dutch equally "proud and treacherous", a stereotype for African-born slaves.[5] The Dutch West India Company immune New Netherlanders to trade slaves from Angola for "seasoned" African slaves from the Dutch West Indies, specially Curaçao, who sold for more than other slaves. They besides bought slaves that came from privateers of Spanish slave ships.[five] For case, La Garce a French privateer, arrived in New Amsterdam in 1642 with Spanish Negroes that were captured from a Spanish send. Although they claimed to be free, and not African, the Dutch sold them as slaves due to their skin color.[6]

Slaves in the n were often owned by notable people like Benjamin Franklin, William Penn and John Hancock. In New Amsterdam, William Henry Seward grew up in a slave-owning family. Confronting slavery, he became Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of Land during the Civil War.[eight]

Unique to slaves from other colonies, slaves could sue another person whether white or black. Early instances included suits filed for lost wages and damages when a slave'due south dog was injured past a white human being's dog. Slaves could also be sued.[b]

Partial and full freedom [edit]

By 1644, some slaves had earned partial liberty, or one-half-freedom, in New Amsterdam and were able to earn wages. Under Roman-Dutch law they had other rights in the commercial economic system, and intermarriage with working-class whites was frequent.[10] State grant records show that State of the Blacks was located just north of New Amsterdam. As the English began to seize New Amsterdam in 1664, the Dutch freed about 40 men and women who had been granted half-slave status, to ensure that the English would not keep them enslaved. The new freemen had their original land grants finalized and all grants were officially marked as owned by the new freemen.[eleven]

English rule [edit]

A 1798 watercolor of Fresh Water Pond. Bayard's Mount, a 110-foot (34 m) hillock, is in the left foreground. Prior to being levelled around 1811 information technology was located near the electric current intersection of Mott and Grand Streets. New York City, which then extended to a stockade which ran approximately north–southeast from today's Chambers Street and Broadway, is visible beyond the southern shore.

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They connected to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a broad diversity of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agronomical areas. In 1703, more than 42% of New York City's households held slaves, a percentage college than in the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, and second only to Charleston in the South.[2]

In 1708, the New York Colonial Associates passed a law entitled "Act for Preventing the Conspiracy of Slaves" which prescribed a death sentence for any slave who murdered or attempted to murder his or her master. This police, one of the first of its kind in Colonial America, was in role a reaction to the murder of William Hallet Iii and his family in Newtown (Queens).[12]

In 1711, a formal slave market was established at the end of Wall Street on the East River, and information technology operated until 1762.[13]

An act of the New York General Assembly, passed in 1730, the concluding of a serial of New York slave codes, provided that:

Forasmuch as the number of slaves in the cities of New York and Albany, every bit too within the several counties, towns and manors inside this colony, doth daily increment, and that they have oftentimes been guilty of confederating together in running away, and of other ill and unsafe practices, be it therefore unlawful for above 3 slaves to meet together at any time, nor at any other place, than when it shall happen they see in some servile employment for their masters' or mistresses' profit, and past their masters' or mistresses' consent, upon penalisation of being whipped upon the naked back, at the discretion of any 1 justice of the peace, not exceeding forty lashes for each criminal offense.[14]

Manors and towns could engage a common whipper at no more than 3 shillings per person.[xv] Blacks were given the lowest status jobs, the ones the Dutch did non want to perform, like meting out corporal penalization and executions.[sixteen]

As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept past periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the New York Conspiracy of 1741, city officials believed a revolt had started. Over weeks, they arrested more 150 slaves and twenty white men, trying and executing several, in the conventionalities they had planned a revolt. Historian Jill Lepore believes whites unjustly accused and executed many blacks in this outcome.[17]

In 1753, the Assembly provided there should be paid "for every negro, mulatto or other slave, of iv years old and upwards, imported directly from Africa, v ounces of Sevil[le] Pillar or Mexico plate [silvery], or 40 shillings in bills of credit made current in this colony."[18]

American Revolution [edit]

Runaway slave advert (1774).

African Americans fought on both sides in the American Revolution. Many slaves chose to fight for the British, equally they were promised liberty by General Guy Carleton in exchange for their service. After the British occupied New York City in 1776, slaves escaped to their lines for freedom. The black population in New York grew to x,000 by 1780, and the urban center became a center of free blacks in North America.[10] The fugitives included Deborah Squash and her married man Harvey, slaves of George Washington, who escaped from his plantation in Virginia and reached freedom in New York.[10]

In 1781, the country of New York offered slaveholders a fiscal incentive to assign their slaves to the armed forces, with the promise of freedom at war's terminate for the slaves. In 1783, black men made up one-quarter of the rebel militia in White Plains, who were to march to Yorktown, Virginia for the last engagements.[ten]

By the Treaty of Paris (1783), the United States required that all American property, including slaves, exist left in place, but General Guy Carleton followed through on his commitment to the freedmen. When the British evacuated from New York, they transported 3,000 Blackness Loyalists on ships to Nova Scotia (at present Maritime Canada), every bit recorded in the Volume of Negroes at the National Archives of Great United kingdom and the Black Loyalists Directory at the National Archives at Washington.[10] [19] With British support, in 1792 a large group of these Black Britons left Nova Scotia to create an contained colony in Sierra Leone.[20]

Gradual abolition [edit]

In 1781, the state legislature voted to gratuitous those slaves who had fought for three years with the rebels or were regularly discharged during the Revolution.[21] The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, and worked to prohibit the international slave trade and to attain abolition. It established the African Gratuitous Schoolhouse in New York City, the beginning formal educational establishment for blacks in North America. Information technology served both free and slave children. The school expanded to seven locations and produced some of its students advanced to higher education and careers. These included James McCune Smith, who gained his medical caste with honors at the University of Glasgow later on being denied comprisal to two New York colleges. He returned to practice in New York and also published numerous articles in medical and other journals.[10]

Past 1790, one in three blacks in New York state were gratis. Especially in areas of concentrated population, such as New York City, they organized as an independent customs, with their own churches, benevolent and civic organizations, and businesses that catered to their interests.[10]

Although there was motility towards abolition of slavery, the legislature took steps to characterize indentured servitude for blacks in a way that redefined slavery in the land. Slavery was important economically, both in New York City and in agricultural areas, such as Brooklyn. In 1799, the legislature passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. It freed no living slave. It alleged children of slaves born afterward July iv, 1799, to be legally gratuitous, but the children had to serve an extended catamenia of indentured servitude: to the age of 28 for males and to 25 for females. Slaves born before that date were redefined as indentured servants and could non be sold, but they had to continue their unpaid labor.[22] From 1800 to 1827, white and blackness abolitionists worked to terminate slavery and achieve full citizenship in New York. During this fourth dimension, there was a rise in white supremacy, which was at odds with the increased anti-slavery efforts of the early 19th century.[23] Peter Williams Jr., an influential black abolitionist and minister, encouraged other blacks to "by a strict obedience and respect to the laws of the land, form an invulnerable barrier confronting the shafts of malice" to better the chances of liberty and a better life.[24]

African-Americans' participation equally soldiers in defending the state during the War of 1812 added to public support for their full rights to freedom. In 1817, the state freed all slaves born before July 4, 1799 (the date of the gradual abolition law), to exist constructive in 1827. It continued with the indenture of children born to slave mothers until their 20s, equally noted above.[22] Because of the gradual abolition laws, there were children all the same bound in apprenticeships when their parents were free.[25] This encouraged African-American anti-slavery activists.[25]

In Sketches of America (1818), British author Henry Bradshaw Fearon, who visited the young United States on a fact-finding mission to inform Britons considering emigration, described the situation in New York Metropolis equally he constitute it in Baronial 1817:

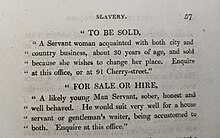

Advertisements for slaves in the New York Daily Advertiser in 1817, equally reproduced in Henry Bradshaw Fearon'south Sketches of America (1818).

New York is chosen a "free land:" that it may be and then and then theoretically, or when compared with its southern neighbors; just if, in England, nosotros saw in the Times newspaper such advertisements as the following [meet paradigm to right], nosotros should conclude that freedom from slavery existed only in words.[26]

On July 5, 1827, the African-American customs celebrated final emancipation in the state with a parade through New York City.[24] [27] July 5 was called over July iv, because the national holiday was not meant for blacks, as Frederick Douglass stated in his famous What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? speech of July 5, 1852.[27]

Right to vote [edit]

New York residents were less willing to give blacks equal voting rights. By the constitution of 1777, voting was restricted to free men who could satisfy certain belongings requirements for value of existent estate. This property requirement disfranchised poor men among both blacks and whites. The reformed Constitution of 1821 eliminated the property requirement for white men, just set a prohibitive requirement of $250 (equivalent to $5,000 in 2020), virtually the price of a pocket-sized house,[28] for black men.[22] In the 1826 election, but sixteen blacks voted in New York Urban center.[3] : 47 "As late as 1869, a majority of the state'due south voters cast ballots in favor of retaining belongings qualifications that kept New York's polls closed to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, in 1870."[22]

Freedom'due south Journal [edit]

The kickoff issue of the Freedom's Journal, the starting time African-American paper, on March sixteen, 1827

Beginning March xvi, 1827, John Brown Russwurm published Freedom's Periodical, written by and directed to African Americans.[29] [30] Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm were editors of the journal; they used information technology to appeal to African Americans across the nation.[31] The powerful words published spread rapid positive influence to African Americans who could assist institute a new community. The emergence of an African-American journal was a very important movement in New York. It showed that blacks could proceeds education and be part of literate lodge.[32]

White newspapers published a fictional "Bobalition" print series. This was fabricated in mockery of blacks, using the way an uneducated colored person would pronounce abolition.[33]

Involvement in the illegal slave trade [edit]

First in the early on 1850s, New York City became a central center for the Atlantic slave trade, which Congress had banned in 1807. The main slave traders arrived in Manhattan during this catamenia from Brazil and Africa, and became known as the Portuguese Company. Two of the cardinal traffickers were Manoel Basilio da Cunha Reis and Jose Maia Ferreira.[ commendation needed ] They posed as merchants in legal trade but in fact bought upward vessels which they sent to the African coast, usually the Congo River region. The vast majority of vessels were ultimately bound for Cuba. In total over 400 illegal slave vessels left the The states during this catamenia, the vast bulk from New York, although others departed from New Orleans, Boston, and other minor ports. This merchandise was enabled by American captains and sailors, corrupt U.S. officials in New York, and by the ruling Democratic Party, which had limited involvement in suppressing the trade.

African Burial Basis [edit]

In 1991, a construction project required an archaeological and cultural study of 290 Broadway in Lower Manhattan to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 before construction could begin. During the excavation and study, human being remains were plant in a former vi-acre burial basis for African Americans that dated from the mid-1630s to 1795. It is believed that there are more than than 15,000 skeletal remains of colonial New York'due south free and enslaved blacks. Information technology is the country'southward largest and earliest burial ground for African-Americans.[34]

This discovery demonstrated the big-scale importance of slavery and African Americans to New York and national history and economy. The African Burial Basis has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and a National Monument for its significance. A memorial and interpretive middle for the African Burial Ground accept been created to honour those buried and to explore the many contributions of African Americans and their descendants to New York and the nation.[35]

See also [edit]

- African Americans in New York City

- African Burial Basis National Monument

- New York Conspiracy of 1741

- Human trafficking in New York

- Rose Butler

- Sylvester Manor

Notes [edit]

- ^ The Dutch engaged in battles with the Castilian and French every bit they sought to accept a hold on the slave trade and they would keep people of color as war prizes, with no stardom between those who may accept been slaves, and those who were free crew members.[6]

- ^ On December 9, 1638, a slave known as Anthony the Portuguese sued a white merchant, Anthony Jansen from Salee, and was awarded reparations for amercement caused to his hog by the defendant's canis familiaris. In the following twelvemonth Pedro Negretto successfully sued an Englishman, John Seales, for wages due for tending hogs. Manuel de Reus, a servant of the Director General Willem Kieft, granted a power of attorney to the commas at Fort Orange to collect fifteen guilders in back wages for him from Hendrick Fredricksz." Unique to this colony was how penalty could be given to a Slave. In this instance he was suited, "...in 1639 a white merchant Jan Jansen Damen, sued Trivial Manuel (sometimes called Manuel Minuit) and was in turn sued past Manuel de Reus; both cases were settled out of court."[ix]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Harper, Douglas (2003). "Emancipation in New York". Slavery in the N.

- ^ a b Oltman, Adele (November seven, 2005). "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York". The Nation.

- ^ a b Foner, Eric (2015). Gateway to Freedom. The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN9780393244076.

- ^ a b c Hodges, Graham R.G (2005). Root and Co-operative: African Americans in New York and East New Jersey, 1613-1863. U. of North Carolina Press. ISBN9780807876015 . Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Harper, Douglas (2003). "Slavery in New York". Slavery in the North. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Leslie Grand. (2004-08-01). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. University of Chicago Printing. pp. 18–19. ISBN978-0-226-31775-5.

- ^ Harris, Leslie K. (2004-08-01). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. University of Chicago Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN978-0-226-31775-5.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2003). "Slavery in the N". Slavery in the North . Retrieved March sixteen, 2020.

- ^ Faucquez, Anne-Claire (2019). "Corporate Slavery in Seventeenth-Century New York" in Catherine Armstrong, The Many Faces of Slavery. New Perspectives on Slave Buying and Experiences in the Americas. Bloomsbury. ISBN9781350071445 . Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Exhibit: Slavery in New York". New York Historical Society. Oct 2005. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ^ Peter R. Christoph, "Freedmen of New Amsterdam", Selected Rensselaerwicjk Papers, New York State Library, 1991

- ^ Wolfe, Missy. Insubordinate Spirit: A Truthful Story of Life and Loss in Earliest America 1610-1665. Guilford CT, 2012, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Philip, Abby. "A permanent reminder of Wall Street'south hidden slave-trading by is coming soon", Washington Post, April 15, 2015, retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Dillon, John Brown (1879). Oddities of Colonial Legislation in America: As Applied to the Public Lands, Primitive Education, Faith, Morals, Indians, Etc., with Accurate Records of the Origin and Growth of Pioneer Settlements, Embracing As well a Condensed History of the States and Territories. R. Douglass. pp. 225–226.

- ^ Weise, Arthur James (1880). History of the seventeen towns of Rensselaer County, from the colonization of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck to the nowadays time. Troy, New York: Troy, Northward. Y., Francis & Tucker. p. six.

- ^ Harris, Leslie G. (2004-08-01). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. University of Chicago Press. p. 20. ISBN978-0-226-31775-5.

- ^ Lepore, Jill, New York Called-for; Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, 2005.

- ^ Excise, New York (State) Department of (1897). Almanac Written report of the State Commissioner of Excise of the State of New York. Department of Excise. p. 523.

- ^ "African Nova Scotians". March 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ The Journal of Negro History. United Pub. Corporation. 1922. p. 184.

- ^ Eisenstadt, Peter (2005-05-19). Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse University Press. p. 19. ISBN978-0-8156-0808-0.

- ^ a b c d "African American Voting Rights" Archived November 9, 2010, at the Library of Congress Spider web Archives, New York State Archives, retrieved February 11, 2012

- ^ Gellman, David N. (August 2008). Emancipating New York: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom, 1777–1827. LSU Press. p. x. ISBN978-0-8071-3465-eight.

- ^ a b Peterson, Carla L. (2011-02-22). Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City. Yale University Press. p. 1826. ISBN978-0-300-16409-1.

- ^ a b Harris, Leslie M. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York Metropolis, 1626–1863. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003: 93–95.

- ^ Fearon, Henry Bradshaw (1818). Sketches of America: A Narrative Journey of V M Miles Through the Eastern and Western States. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. pp. 56–57. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Sinha, Manisha (2016-02-23). The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolitionism. Yale University Press. p. 201. ISBN978-0-300-18208-8.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2003). "Emancipation in New York".

- ^ Hodges, Graham Russell (2010). David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City. Univ of Northward Carolina Printing. p. 33. ISBN978-0-8078-3326-i.

- ^ Penn, Irvine Garland (1891). The Afro-American Printing and Its Editors. Willey & Company. pp. 26.

- ^ Capie, Julia M. "Freedom of Unspoken Voice communication: Implied Defamation and Its Constitutional Limitations". Touro Law Review 31, no. iv (October 2015): 675.

- ^ Gellman, David N. "Race, the Public Sphere, and Abolitionism in Tardily Eighteenth-Century New York," Periodical of the Early Republic 20, no. 4 (2000): 607–36.

- ^ "Bobalition of slavery". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 United states of america . Retrieved 2020-11-16 .

- ^ "History & Culture - African Burying Basis National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service . Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ "African Burial Footing National Monument", National Park Service; retrieved Dec 29, 2007

Further reading [edit]

- Bruno, Debra (July 22, 2020). "History Lessons". Washington Post.

- Oltman, Adele (November 5, 2007). "The Subconscious History of Slavery in New York". The Nation.

- Harris, John (2020). The Last Slave Ships: New York and the End of the Center Passage. ISBN978-0300247336.

External links [edit]

- Slavery in New York, October 2005 – September 2007, an exhibition by the New-York Historical Society

- "Interview: James Oliver Horton: Exhibit Reveals History of Slavery in New York Urban center", PBS Newshour, Jan 25, 2007

- Slavery In Mamaroneck Township, Larchmont Website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_slavery_in_New_York_%28state%29

0 Response to "Born to Run: the Slave Family in Early New York"

Post a Comment