Mythological Creatures Who Can Rise Again

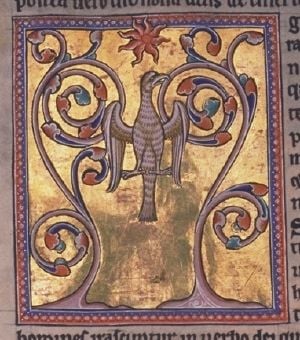

The phoenix from the Aberdeen Bestiary.

The phoenix, or phœnix equally it is sometimes spelled, has been an enduring mythological symbol for millennia and across vastly different cultures. Despite such varieties of societies and times, the phoenix is consistently characterized every bit a bird with brightly colored plumage, which, after a long life, dies in a fire of its own making only to rise again from the ashes. From religious and naturalistic symbolism in aboriginal Egypt, to a secular symbol for armies, communities, and even societies, besides as an often-used literary symbol, this mythical bird'due south representation of death and rebirth seems to resonate with humankind's aspirations.

Contents

- 1 General Description

- 2 Mythical Origins

- ii.ane Egyptian

- ii.ii Western farsi

- 2.iii Greek

- 2.four Oriental

- 2.5 Judaism and Christianity

- three Heraldry

- 4 Literature

- v Notes

- 6 References

- vii External links

- eight Credits

General Description

Although many cultures have their own interpretation of the phoenix, the differences in nuance are overshadowed by the mythical beast'due south more homogeneous characteristics. The phoenix is always a bird, usually having plumage of colors corresponding to fire: yellow, orange, blood-red, and gold. The most universal characteristic is the bird'southward ability to resurrect. Living a long life (the exact age tin vary from v hundred to over a 1000 years), the bird dies in a cocky-created fire, burning into a pile of ashes, from which a phoenix chick is born, representing a cyclical process of life from death. Because it is reborn from its ain death, the phoenix also took on the characteristics of regeneration and immortality.

Did you know?

Diverse cultures include variations on the phoenix, a bird with the ability to be reborn

Mythical Origins

Egyptian

The primeval representation of the phoenix is found in the aboriginal Egyptian Bennu bird, the proper name relating to the verb "weben," significant "to rise brilliantly," or "to shine." Some researchers believe that a at present extinct big heron was a possible existent life inspiration for the Bennu. However, since the Bennu, like all the other versions of the phoenix, is primarily a symbolic icon, the many mythical sources of the Bennu in ancient Egyptian civilisation reveal more most the civilization than the being of a real bird.

I version of the myth says that the Bennu bird burst along from the heart of Osiris. In the more than prevalent myths, the Bennu created itself from a fire that was burned on a holy tree in i of the sacred precincts of the temple of Ra. The Bennu was supposed to take rested on a sacred colonnade that was known equally the benben-stone. At the end of its life-cycle, the phoenix would build itself a nest of cinnamon twigs that it then ignited; both nest and bird burned fiercely and would be reduced to ashes, from which a new, young phoenix arose. The new phoenix embalmed the ashes of the one-time phoenix in an egg made of myrrh and deposited it in the Egyptian urban center of Heliopolis ("the city of the dominicus" in Greek).

The Bennu was pictured as a grey, purple, bluish, or white heron with a long beak and a 2-feathered crest. Occasionally information technology was depicted as a yellowish wagtail, or every bit an eagle with feathers of blood-red and gilded. In rare instances the Bennu was pictured equally a man with the caput of a heron, wearing a white or blue mummy dress under a transparent long glaze. Because of its connexion to Egyptian organized religion, the Bennu was considered the "soul" of the god Atum, Ra, or Osiris, and was sometimes called "He Who Came Into Being past Himself," "Ascending 1," and "Lord of Jubilees." These names and the connection with Ra, the sunday god, reflected non just the aboriginal Egyptian belief in a spiritual continuation of life after physical expiry, but also reflected the natural process of the Nile River's rise and falling, which the Egyptians depended upon for survival. The Bennu likewise became closely connected to the Egyptian calendar, and the Egyptians kept intricate fourth dimension measuring devices in the Bennu Temple.

Persian

The Huma, also known as the "bird of paradise," is a Farsi mythological bird, similar to the Egyptian phoenix. It consumes itself in fire every few hundred years, only to rise anew from the ashes. The Huma is considered to be a compassionate bird and its bear upon is said to bring bang-up fortune.

The Huma bird joins both the male and female natures together in ane body, each sharing a wing and a leg. Information technology avoids killing for nutrient, rather preferring to feed on feces. The Persians teach that dandy blessings come to that person on whom the Huma's shadow falls.[1]

According to Sufi master Hazrat Inayat Kahn,

The word huma in the Persian language stands for a fabulous bird. There is a conventionalities that if the huma bird sits for a moment on someone'southward head it is a sign that he volition get a rex. Its true significant is that when a person's thoughts evolve and so that they interruption all limitation, he then becomes a king. It is the limitation of language that it can only describe the Nearly Loftier every bit something similar a rex.[ii]

Greek

The Greeks adapted the word bennu and identified it with their ain word phoenix 'φοινιξ', pregnant the color regal-red or ruby-red. They and the Romans later pictured the bird more like a peacock or an eagle. According to Greek mythology, the phoenix lived in Arabia adjacent to a well. At dawn, it bathed in the water of the well, and the Greek sun-god Apollo stopped his chariot (the dominicus) in order to mind to its song.

Oriental

The phoenix (known as Garuda in Sanskrit) is the mystical fire bird which is considered as the chariot of the Hindu god Vishnu. Its reference tin exist establish in the Hindu ballsy Ramayana.

In Red china, the phoenix is called Feng-huang and symbolizes completeness, incorporating the basic elements of music, colors, nature, as well as the joining of yin and yang. It is a symbol of peace, and represents fire, the sun, justice, obedience, and allegiance. The Feng-huang, unlike the phoenix which dies and is reborn, is truly immortal although it just appears in times of peace and prosperity.[3]

Judaism and Christianity

In Judaism, the phoenix is known as Milcham or Chol (or Hol): The story of the phoenix begins in the Garden of Eden when Eve fell, tempted past the ophidian to consume the forbidden fruit. According to the Midrash Rabbah, upset by her situation and jealous of creatures still innocent, Eve tempted all the other creatures of the garden to do the aforementioned. Merely the Chol (phoenix) resisted. Every bit a advantage, the phoenix was given eternal life, living in peace for a m years and so beingness reborn from an egg to proceed to live in peace again, repeating the cycle eternally (Gen. Rabbah 19:5). Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, better known as Rashi, commented that decease has no power over the phoenix, "considering information technology did not taste the fruit from the tree of knowledge."[iv]

The phoenix also appears in the Book of Job: "I shall multiply my days as the Chol, the phoenix" (Task 29:18), again indicating long life if not immortality. This reference, notwithstanding, is controversial since chol has been translated as phoenix, sand, and palm tree in different versions.[five]

The phoenix became a symbol of Christianity in early literature, either from the ancient Hebrew legend or from the incorporation of Greek and Roman culture, or from a combination of both. In any case, the ideology of the phoenix fit perfectly with the story of Christ. The phoenix's resurrection from death as new and pure can be viewed as a metaphor for Christ's resurrection, central to Christian conventionalities. The phoenix is referenced past the early Christian Apostolic Begetter Clement in The Starting time Epistle of Cloudless to the Corinthians. Most of the Christian-based phoenix symbolism appears inside works of literature, specially in Medieval and Renaissance Christian literature that combined classical and regional myth and folklore with more mainstream doctrine.

Heraldry

Rinasce piu gloriosa ("It rises again more glorious").

The phoenix does not appear as a heraldic figure as oft as other mythical creatures. However, it has appeared on family crests and shields throughout time, usually depicted as an eagle surrounded, but not hurt, past flames. Jane Seymour's heraldic bluecoat includes a phoenix rising from a castle, between two ruddy and white Tudor roses.[6] Some cities in Europe use the phoenix in their municipal keepsake to denote the one-time destruction and consequent rebuilding of the urban center, connecting to the image of resurrection inherent in the phoenix.

Phoenix, Arizona was named such because it was a frontier station settled upon the ruins of a Native American site. The start European inhabitants decided to name their city in concurrence with the idea that from the ruins of 1 urban center, another was created.

Literature

A reborn Phoenix, rise from its ashes.

The phoenix no longer appears significantly in any religious or cultural truths. However, the paradigm is still used in literature, perchance because of all the mythical creatures from antiquity, the phoenix is the ane that frequently expresses an enduring sense of hope and redemption. Its beauty is not as otherworldly as almost of the other creatures in myth, and its symbolism is conveyed with a profound subtlety when used in literature.

William Shakespeare fabricated 1 of the about prominent references in both his plays The Tempest, incorporating a number of other mythical creatures simply placing the phoenix dissever and above the rest, and in Timon of Athens, when a senator metaphorically calls Timon "a naked gull, which flashes now a phoenix." In other works of Renaissance literature, the phoenix is said to have been eaten equally the rarest of dishes—for only one was live at any one fourth dimension. Ben Jonson, in Volpone (1605) writes: "could nosotros become the phœnix, though nature lost her kind, shee were our dish."

Sylvia Townsend Warner's 1940 short story "The Phoenix" satirized the exploitation of nature using a phoenix maltreated in a carnival sideshow, revealing the modern preference for violence and sensationalism over beauty and dignity. The majesty of Eudora Welty's archetype 1941 brusk story "A Worn Path" employs the phoenix as the name of the major and near sole character of a sparsely written, yet rich story of regeneration and the South.

Edith Nesbit's famous children'southward novel, The Phoenix and the Carpet is based on this legendary creature and its quirky friendship with a family of children. The phoenix was too famed for being a symbol of the rising and fall of society in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. The pattern of an over conceited and abusive society'due south devastation yielding a fresh new start was compared to the phoenix's mythological blueprint of consumption by flame, so resurrection out of ashes.

Sylvia Plath also alludes to the phoenix in the end of her famous poem Lady Lazarus. The speaker of this poem describes her unsuccessful attempts at committing suicide not as failures, but as successful resurrections, similar those described in the tales of the biblical character Lazarus and the phoenix. By the end of the verse form, the speaker has transformed into a fire bird, effectively marking her rebirth, which some critics liken to a demonic transformation. The poem ends: "Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men similar air."

More recently, Harry Potter series writer J.Yard. Rowlings has used a phoenix as a central symbol in her stories. While the Harry Potter series has drawn some controversy from the Christian customs, Rowling's employ of other classical mythical beasts and her classical literature background suggests that she is using the phoenix as a Christian symbol of purification and resurrection.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Naosherwan Anzar (transl.), The Master Sings, Meher Baba's Ghazals (Zeno Publishing Services, 1981). On-line edition, May 28, 1995. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ Kahn, Hazrat Inayat, The Music of Life (Omega Publications, 1998, ISBN 978-0930872380).

- ↑ Mark Schumacher, Phoenix www.onmarkproductions.com. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ Legends of the Phoenix: A Basis in Biblical History Countdown to the Messiah. Retrieved May xiii, 2011.

- ↑ George Sajo, Phoenix on the top of the palm tree: Multiple interpretations of Job 29:18 Silva de varia leccion, Studiolum, 8-2-2005. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ Tudor Heraldic Badges Coats of Arms & Their Meanings The Tudors wiki. Retrieved Apr 29, 2015.

- ↑ John Granger, Looking for God in Harry Potter (Saltriver, 2006, ISBN 1414306342).

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Conway, D. J. Magickal Mystical Creatures: Invite Their Powers Into Your Life. Llewellyn Publications, 2001. ISBN 156718149X

- Granger, John. Looking for God in Harry Potter. SaltRiver, 2006. ISBN 978-1414306346

- Kahn, Hazrat Inayat. The Music of Life. Omega Publications, 1998. ISBN 978-0930872380

- Nigg, Joe. Wonder Beasts: Tales and Lore of the Phoenix, the Griffin, the Unicorn, and the Dragon. Libraries Unlimited, 1995. ISBN 156308242X

External links

All links retrieved March 25, 2019.

- Phoenix (Bennu, Benu) Ancient Egypt: The Mythology

- Phoenix – Entry in The Aberdeen Bestiary

- Phoenix The Medieval Bestiary

- Phoenix (mythology)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia commodity in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-past-sa 3.0 License (CC-past-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that tin reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Phoenix_(mythology) history

- Bennu history

- Huma_(mythology) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New Globe Encyclopedia:

- History of "Phoenix (mythology)"

Note: Some restrictions may employ to utilise of individual images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Phoenix_(mythology)

0 Response to "Mythological Creatures Who Can Rise Again"

Post a Comment